Last month creative Berlin-based startup How.Do announced it was closing, and today, June 30th, marks the end of their journey. Despite a short lifetime, the company’s achievements and potential, which inspired a huge network of makers, seemed to merit the obituary of a long, well-lived life. If you believe in life after death, do you ever wonder where the spirit of a startup goes?

How.Do is – or was – a platform started in 2012 in Stockholm for sharing micro-knowledge, that is to say an app for recording photos with up to eight seconds of audio to create chapters of a How.Do, a way of sharing everyday knowledge in a beautifully simple way.

How.Do wasn’t originally supposed to be an app. It was concocted like a potion, with ideas, academic theories and philanthropic desires stirred into it, but when the founders Emma Rose Metcalfe and Nils Westerlund concluded that the tools needed to share knowledge were a camera and a microphone, they concluded that everyone carries these tools around all the time.

How.Do founders Emma Rose Metcalfe, Edward Jewson and Nils Westerlund at the Maker Faire, New York

Metcalfe, from the north of England, came from a background in service design amongst other things, and has all kinds of unusual stories to tell such as the period of her life when she lived in a cabin in the woods. Westerlund, on the other hand, was an expert in sound, very data-driven and had been working at SoundCloud, the darling of Berlin’s startup scene. It was on a study trip to India as part of their Masters that the pair realised they wanted to work on something together, combining sound and image to create an experience that’s meaningful.

Their academic approach is immediately obvious if you speak to either of them about How.Do – the choice to make the audio eight seconds per chapter was drawn from research at the time about learning, memory and our ever decreasing attention spans. Both founders were fascinated by what Metcalfe refers to as the “emotional durability of sound”, and they remained concerned during the lifespan of How.Do that content should have a longer term social value, rather than appear fleetingly on a homefeed.

“Oh shit we made a company”

Suddenly what had been a study project had gained momentum, and they’d already brought on Edward Jewson as a co-founder and CTO, who pushed out a beta product for friends to experiment with. Friends and acquaintances asked regularly when to expect a new release, and Metcalfe explains that this was empowering and encouraging, but they said to themselves “Oh shit we made a company. What do we need to learn now?”. Metcalfe soon found she was at risk of failing her Masters degree due to pouring her energies into How.Do, and during a crisis meeting with her professor it was suggested that she should combine the two, resulting in her degree being on the meaningful distribution of experiences. They had to start behaving more like they were running a business, rather than like students, which meant following in the footsteps of other startups.

Invites to beta test How.Do

In May 2012 they registered as a limited company in the UK while still based in Stockholm, with the rather charming name How Do You Peel A Banana? Ltd, and at the end of the summer they raised a significant seed round and officially launched How.Do. The funding came from Horizon Ventures, Peter Read (an angel investor in the UK who also invested in another creative startup which later failed, Gidsy), and Wellington Partners, which praised the How.Do founders’ “extraordinary vision”. People had faith in the company and the product. One of the founders’ mentors Henrik Torstensson, who was the head of marketing at Spotify, had used the app silently while the founders watched him and anticipated his opinion. After what felt to them like an interminable wait, he simply said, “There’s some kind of weird magic in this. I can’t tell what it is”. Alex Ljung, co-founder of SoundCloud, was also impressed, stating “That’s the magic of sound right there”.

I’m a dreamer

With gold lining their pockets and ready to scale their business, they continued their journey on the startup trajectory. The team moved from their living room in Stockholm to Berlin, a cheaper hub of creativity, and found it suited them well to be amongst a keen ‘maker’ community. At first they shared an office with other startups at the Wostel, a coworking space in the trendy, low-rent area of Neukölln in the south of the city. The Wostel has also previously housed other popular Berlin startups Amen (which has since disappeared) and Loopcam, and out in the back yard sits Hüttenpalast, an unusual hotel of caravans and dens where dreamers can roost for a weekend.

What lay ahead was endless potential. The founders drew up a list on the wall of who they would love to employ, and were unafraid to approach anyone, finding that everyone was accessible and happy to have a chat: “It was incredible,” they breathe. They set about assembling their fantasy team, employing creative spirits from Italy, the UK and even flying a software engineer over from Argentina. They listened to feedback about the app, they iterated and they analysed. Co-founder Westerlund says “We were tracking every move of our users in closed beta”, aiming to understand how people used the product, what users wanted out of it, and learning in the process what the constituted the “right information” to track.

Despite being another app on people’s smartphone, How.Do cultivated an incredibly passionate community. The team hosted regular ‘Fix-It Nights’ where strangers and friends met to help each other fix broken things. There was no pressure put on attendees to create a How.Do tutorial while they were there, about for example ‘How do you solder wires to fix a broken electrical cord?’ which I learned from a friendly stranger. They cut up their pizza with scissors, shared beers amongst their disciples and spread a lot of positivity and human kindness in the process. Their app, after all, was to “empower people to empower people” as Metcalfe described their philanthropic leaning.

How.Do captured the imagination of the maker community

How.Do’s efforts gained support and encouragement from other startups which are now enjoying success and wider recognition, such as Sugru and photography app EyeEm. How.Do did not garner as much media attention as these peers, though tech website GigaOM profiled the app. David Meyer, the journalist who wrote the piece, described the app – which admittedly went on to be improved in functionality – as being “not quite there yet”. He also said that it was “maddeningly close to be something else” and that “there’s something in this thing”, which seemed to ring true even as the company started to wind down recently. There was some kind of weird magic in there.

“We almost made it work”

Interestingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, research this year has shown that startups that fail tend to end 20 months after their last round of investment. How.Do raised in October 2012, and is now closing exactly 20 months later. It would be easy to dismiss How.Do, treat the failure as an inevitability; another casualty of the bloodthirsty startup scene. It unwittingly fell into the grooves left by other failed businesses. But How.Do just didn’t fit the mould of being a ‘tech startup’. It broke the rules in a sphere that is all about breaking the rules. Trying to fit How.Do into the tech startup straitjacket is like trying put more and more helium balloons into an unsealed box. There is simply too much colour, and energy, and human emotion bursting out of the sides for it to behave like other businesses.

The app was in some ways superseded by other apps with different purposes but convergent technology such as Vine, which appeared in the early days of How.Do, and using Twitter’s clout and an even easier interface than How.Do, it rocketed in popularity. YouTube, an internet dinosaur compared to How.Do, also improved its offering during How.Do’s lifetime so that viewers could see in a pop up bubble a preview of that section of the video. How.Do had wanted to give users control of video in the same way, to skip forwards, backwards or right to the end to find the part they needed. It’s now hard to believe that YouTube didn’t have this chapter view previously, but this iteration made How.Do a little more redundant. “We almost made it work” says Metcalfe.

Startup graveyard and startup ghosts

Although it is accepted that startups fail, nobody tends to visit the startup graveyard, lay flowers or even celebrate the ideas that were once alive and gleaming. Ideas get dismissed quicker than users delete a ‘has-been’ app from their phones, but these businesses, even if they no longer leave tangible things in their wake, they leave their users behind.

In spring of 2014, the How.Do founders had to make an unpleasant decision and pull the plug. “When we pushed out the blogpost, it was quick. We realised it was really happening”. They began moving out of their office, which by now was in Etsy Germany’s studio in Kreuzberg, Berlin. They sold off their officeware, tables and chairs using a Google spreadsheet to update people as to what had gone already. The official ending day is 30th June, and by the time of the founder interview in early June, it was still unclear what would remain of the technology. The servers, the founders explained, are much too expensive to run to allow people to keep using the How.Do service, so the future availability is uncertain.

For now, the founders are in limbo while the creative spirit dissipates from the business corpse. The feeling of freedom finds them a little uneasy; unsteady on their feet. Metcalfe has been making the most of her differently shaped days, “I can spend my lunchtimes doing whatever the hell I like”, she says, and was pleased to find out that it’s free to watch the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra rehearsing during the day. “There was a man laid down listening to the music with his eyes closed and his shoes off, which is quite fantastic”. As for what’s next, the team members have different plans ahead but for the moment are keeping quiet about where their creativity will manifest itself.

“So that’s what freedom feels like” says Metcalfe, “I don’t know if I like it”.

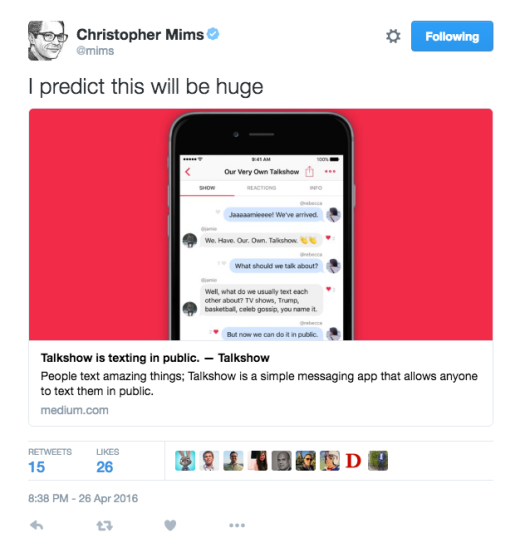

This morning one of the top stories in my Nuzzel newsletter – which puts together the most shared stories from people I follow on Twitter, so that I don’t get FOMO – was about Talkshow, a messaging app that allows you to text publicly.

This morning one of the top stories in my Nuzzel newsletter – which puts together the most shared stories from people I follow on Twitter, so that I don’t get FOMO – was about Talkshow, a messaging app that allows you to text publicly.